The Failed Camden Harbour Settlement

In December 1864 two hundred settlers and their families departed from Victoria in three ships destined for the far side of the country to establish the Camden Harbour Settlement, the first attempt to establish a settlement in the West Kimberley.

They were sold the dream of owning a piece of utopia, settling pastoral land equivalent to nothing before seen in Australia by the Camden Harbour Pastrolist Association founder William Hervey. The land had never been surveyed and descriptions of the area were drawn from glowing reports in explorers' journals three decades earlier, explorers who never actually set foot on the particular patch of country. The settlers came from the areas of Bendigo and Ballarat with little pastoral experience and sold all their belongings for the chance of a life time at Camden Harbour, a patch of land they were told was only 200 miles north from Perth.

They arrived on three ships, with 4500 sheep and 36 horses, 200 settlers amongst 8 families and what awaited them was a disaster from the start.

The first two ships, the Helvitia and the Stagg arrived on the 18th of December. The Stagg had already experienced the first fatality when a settler fell overboard and drowned on the voyage. As the two ships arrived in the heat and humidity of the wet season, the settlers were completely unprepared for what awaited them; dressed in their finest clothes they landed on the shore in the stifling December heat walking through thick mud and stony shores only to find the "finest grazing land" was nothing but a country covered in stones and dust, with very poor drainage for cropping, speargrass that held no nutrition for keeping livestock and the water source being only a small stream five miles inland. Within the first week three settlers had died of heat stroke and as the Stagg sailed from the harbour so did 30 settlers who refused to be left behind.

A week behind the other two ships was the Calliance, which had its first mishap when grounding on Adele Reef. To get the ship off the reef on the next high tide, many of the supplies and belongings had to be thrown overboard in order to float the ship higher. The Calliance sailed into Camden damaged on Christmas Eve. Warned of the disarray on shore and with the Calliance needing repairs before its departure the settlers reluctantly made their way to land. With little knowledge of the tides and no effective leadership, the settlers set straight into establishing dwellings and marking out there portion of land leaving most of their supplies on the shore. As the 9 metre tide rose that day, the remainder of their stores and food supplies were spoiled when they submerged on the muddy banks of the harbour.

By the 5th of January, just over two weeks since the first settlers had arrived, still no reliable water source was found. Of the sheep, who were accustomed to the cool Victorian climate, over 1200 had died of thirst, fly blown or simply malnourished from the lacking sustenance of the dry Kimberley spear grass. Also on the 5th January, the Calliance was to be careened and dried on the dropping tide to inspect and repair the keel. As the tide dropped, a strong gale blew and the ship careened on a boulder breaking her keel in two and wrecking the ship, as the tide rose again it flooded the Calliance up to her top decks.

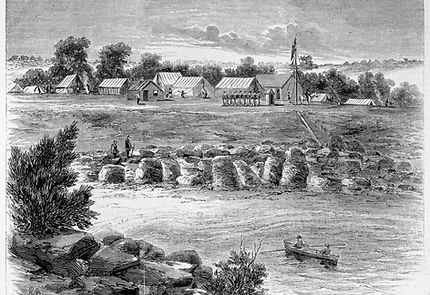

With settlers and stock dying, the situation of the Camden Harbour Settlement became dire and with no firm leadership every family fought for their own best interest. In February, with word reaching West Australian Government - a magistrate, surveyors and police were sent on board the ship Tien Sen to try salvage the settlement and maintain governance. A second government camp was established, wells dug and surveys sent out to find better land but even with all their efforts nothing could stop the stock from dying in their thousands. Willing to lose all their possessions but keep their lives, 70 more settlers abandoned with the Tien Sin. By this time only 80 settlers remained as well as only 1,354 sheep and 26 horses. To make things more difficult the indigenous tribes of the area became hostile as settlers interfered with their lands and battles took place over water sources, stock and stolen property.

Over the coming months the remaining settlers held on until they had assurances from the Government of holding titles elsewhere should they abandon the settlement. Although the weather improved, still the sheep were dropping like flies and settlers continued to pass away through sickness and clashes with the Aborigines. In June Mary Jane Pascoe became the first white woman to die in the Kimberley. She died from ague and complications during child birth, she was buried by her husband on nearby Sheep Island where her headstone still remains today beneath a Boab tree. Days later her new born child passed away.

By October 1865 the government had agreed to resettle the settlers in Cossack, all the stock had died long ago and clashes with the indigenous tribes had become more frequent. The brig, 'Kestrel' evacuated the remaining settlers and government representatives and the settlement was left to be reclaimed by the Kimberley bush.

All that remains today are the few remaining stone walls of the government camp, cleared areas of paths and the dynamite blasted ramp from the waterline for carting stores from the ships' boats. On nearby Sheep Island lays Mary Jane Pascoe's resting place surrounded by six other unmarked graves. On the opposite side of the harbour a small pile of basalt ballast stones remain as the only reminder of the wrecked ship of the Calliance.

Government Camp from our Drone image (top), and image above from State Library Victoria- Government Camp 1865- Copyright expired